Justice Anthony Kennedy retired last month, opening a coveted seat on the Supreme Court to be filled. This past Monday, President Trump named Brett Kavanaugh as Kennedy’s replacement. Kavanaugh is a solidly conservative judge, leaving conservatives celebrating and liberals worrying.

These contrasting reactions show that although justices are not supposed to act with political motivation, it’s easy to tell which are conservative and which are liberal. As justices act independently of their ideologies less and less, the Supreme Court could grow far more political than ever intended, threatening the legitimacy of the institution. So in the era of heightening polarization, it’s worth asking: just how “political” is the court?

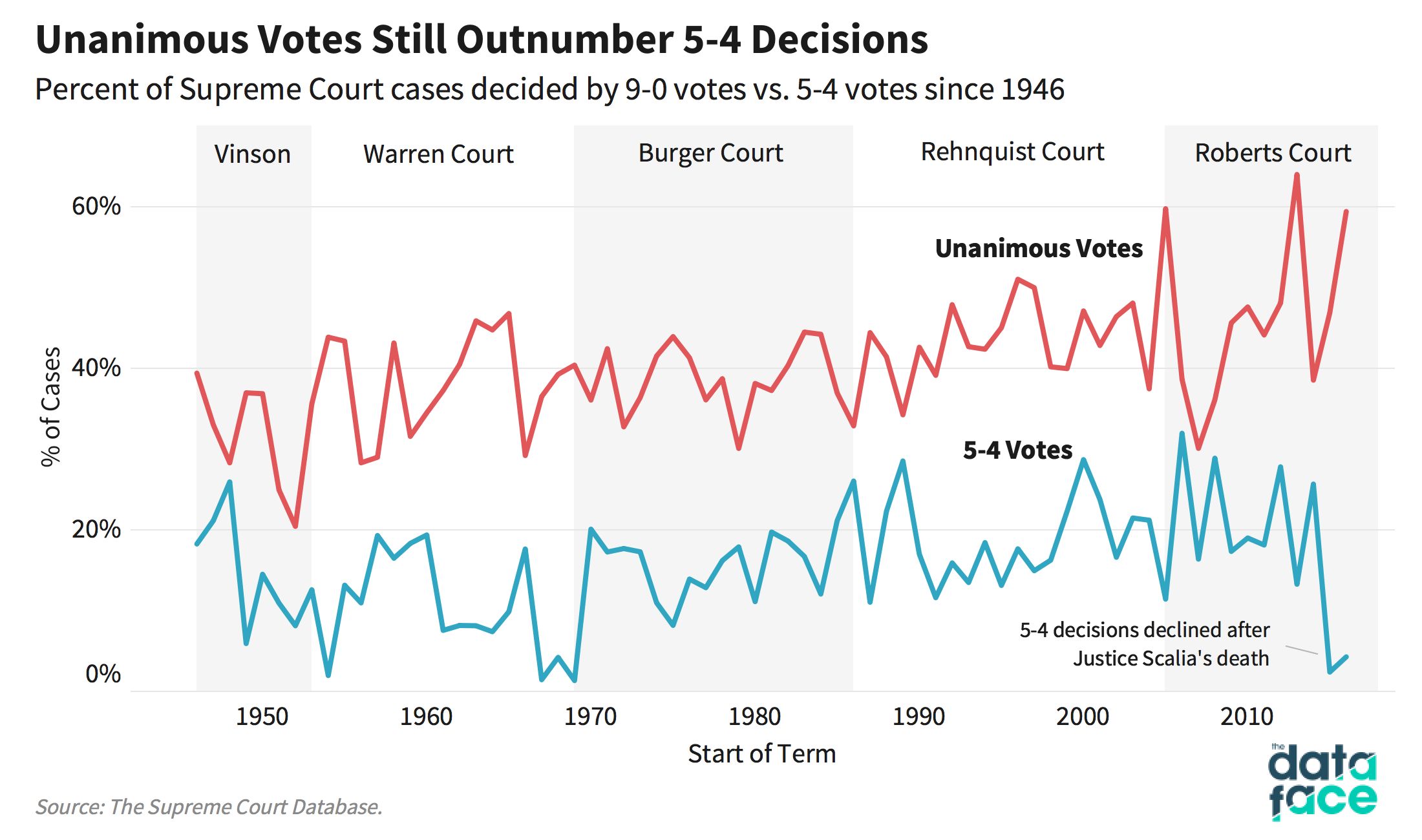

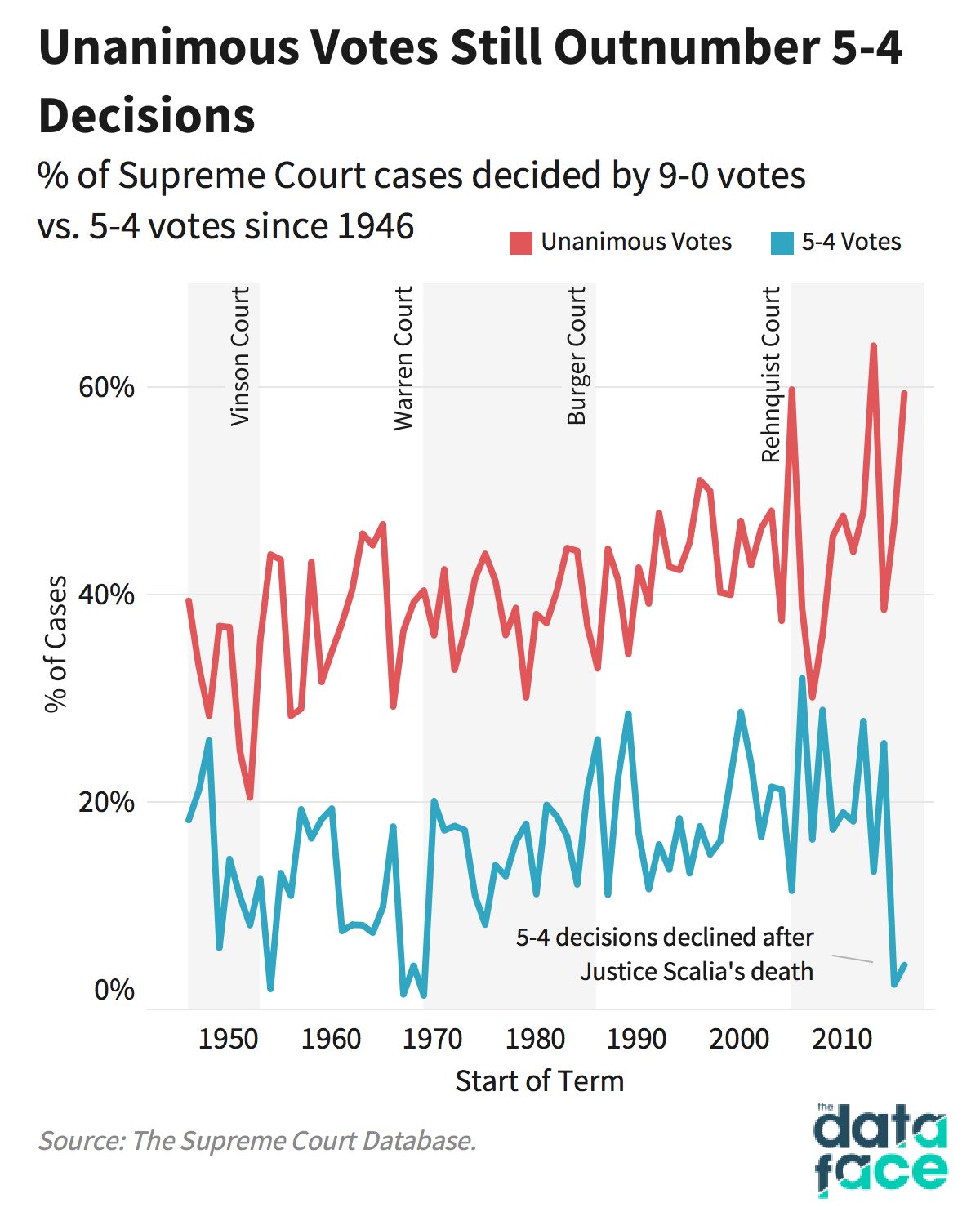

Unanimous Supreme Court Decisions are More Common than 5-4 Votes

The divide within the Supreme Court often manifests itself in cases being decided by contentious 5-4 votes, in which the four liberal justices and four conservative justices vote against each other, previously leaving Kennedy in the middle to cast the deciding vote. A popular narrative is that these close 5-4 votes are growing more common over time, a clear indicator of increasing polarization on the court.

In reality, that narrative is only somewhat true. The occurrence of 5-4 votes are indeed slowly growing over time, yet remain a rarity - only 20% of the court’s cases since 2000 have been decided by a close 5-4 vote. For reference, 17% of cases came to a 5-4 vote between 1988 — the year Kennedy was appointed to the court — and 1999.

Moreover, unanimous 9-0 votes are still more common, as they have been every term in the modern era. Thirty-eight percent of all cases have been decided unanimously since 1988. Thus, the justices of the court come together in complete agreement far more often than they disagree. If this seems surprising, it’s likely because 5-4 votes tend to receive the most media attention, causing the public to perceive contentious votes as being more common than they actually are.

The Majority vs. The Minority

Another measure for overall disagreement in the court is how many more votes the majority voting bloc earns than the minority bloc. The larger the difference, the less the court disagreed over a decision. On the other hand, a difference of just one vote means the court came to a 5-4 vote, showing great contention. If the court truly is becoming more political, we might expect the average difference in voting coalition sizes to trend towards just one vote over time.

In reality, the average difference has slowly grown over time, although it fluctuates. In other words, we’re headed towards slightly more agreeable court decisions, yet inconsistently.

Party-Line Votes in the Supreme Court

Scholars studying Congress often keep track of the frequency of "party-line" votes, which occur when the vast majority of both parties vote together and in opposition to one another. This happened with the Affordable Care Act in 2010, when every single Democrat voted “yes” and every single Republican voted “no.” Party-line votes are an increasingly common phenomena in Congress, symbolizing its growing polarization.

The same concept of voting along party lines can be applied to the court, providing the most accurate test for polarization levels. For the purposes of this study, I’ve defined a Supreme Court party-line vote as when each of the liberal justices and each of the conservative justices cast opposing votes on a case.

To measure ideology, I used Martin-Quinn Scores,which are commonly used to classify justices as conservative or liberal. It should be noted that these scores are not stagnant; justices receive new Martin-Quinn Scores each term, meaning a justice could be classified as conservative in some terms and liberal in others (of course, this would be rare...unless you’re Justice Kennedy).

So are party-line votes in the Supreme Court becoming more common over time?

Cases in which the justices of the court vote completely along ideological lines have become more common over time. However, the trend isn’t linear; the occurrence of party-line votes varies noticeably from year to year, suggesting the court is able to avoid deep polarization, in ways the Congress seems incapable of.

Justice Kennedy’s Absence Will Divide the Supreme Court

Kennedy was usually willing to consider both sides and put his own political preferences aside when casting his vote. His position as the median justice gave him the power to usually cast the crucial deciding voice in most cases that came down to 5-4 votes, earning him his title as "the Decider".

Kennedy’s role as a moderate and his willingness to vote with the liberal justices probably helped keep the court’s polarization in check. In fact, the occasions he crossed ideological lines actually prevented several party-line votes.

If Kennedy had never sat on the Supreme Court and his seat was instead held by a reliable conservative, the court would have seen significantly more party-line votes over the past three decades.

Between Kennedy’s appointment in 1988 and 2016, he voted in 515 cases that came to a 5-4 vote. Of those instances, Kennedy was in the majority 330 times. That’s over 64% of the time, which is significantly more often than the other justices he served with.

Just behind Kennedy is Chief Justice John Roberts, who will become the court’s new median justice assuming Kavanaugh is confirmed by the Senate. Chief Justice Roberts has also played the role of swing voter from time to time, although not nearly as often or reliably as Kennedy. The Supreme Court will likely consist of nine solidly and reliably ideologues following the confirmation of Trump’s nominee, with no clear moderate.

Without a moderate on the court, it’s likely the amount of contentious 5-4 cases will significantly increase. Moreover, with Kennedy’s political moderation being replaced with a much more conservative justice, the delicate balance the court has enjoyed for so long is about to tip to the right. All of this considered, it’s abundantly clear that Kennedy’s retirement will alter the court and the laws of the country for decades to come.

Methodology:

Data over case decisions and justices’ votes comes from The Supreme Court Database.

The Martin-Quinn Score was developed by political scientists Andrew D. Martin and Kevin M. Quinn. Each justice’s score can be found on Martin and Quinn’s website.

Data preparation and analysis can be found on GitHub.